|

A

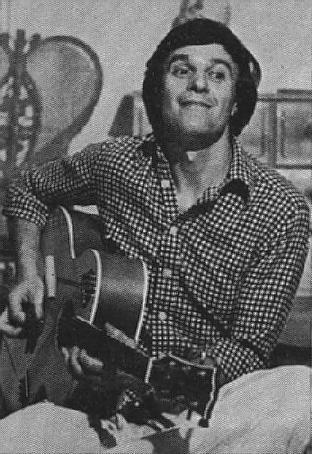

fleet of clouds sails clear of the midday sun, and a klieg from heaven

gleams through the skylight of a Manhattan loft and onto John McLaughlin,

sitting cross-legged on his kitchen counter. Though he emerged last winter

from an eight-year discipleship to the guru Sri Chinmoy, John still

meditates daily and wears the Indian dhoti. At 34, McLaughlin is the Jerry

Brown of music, except that these days he can't get elected - at least on

the pop charts.

To most critics and cognoscenti, though, the British-born McLaughlin is

the most accomplished of all jazz-rock guitarists and an influence

sometimes compared to Coltrane. In performance, with his new group on

campuses and in small clubs, musician friends like Carlos Santana have been

stunned by McLaughlin's dizzying speed and clarity, and his brilliant

fusion of fluttering sitar-like inflections with intricate jazz

improvisation.

He made his name (and up to $20,000 a night) in the early 70s as

Mahavishnu, with a searing, fearsomely loud, electric group called the

Mahavishnu Orchestra and such informative albums as The Inner Mounting

Flame. But McLaughlin has now forsaken all that to gather up three superb

Indian musicians on violin, hand drums and ghatam, and gone into acoustic,

raga-type compositions. Shakti, which translates "creative intelligence

and power" in Sanskrit, is the title of this new group as well as of its

first LP.

A sumptuously spiritual and refined man, McLaughlin shrugs: "Whether

people accept this music or not, I don't give a damn. I know how good - and

how right - this group is. We all sell out to a point. And don't get me

wrong, I like living comfortably and having a nice car. But if money

determines your art, then what's the point?" McLaughlin rents on the

shabby Lower West Side and drives an Audi. He is now just an opening (if

not show-stealing) act for groups like Weather Report, for which his

germinal success with electric jazz-rock helped cut a commercial clearing.

Though he also trailblazed for such major followers as Chick Corea and

former Mahavishnu drummer Billy Cobham, McLaughlin found the genre

ultimately limiting. "You can scream and wail with electric music," he

says. "It has a physical intensity acoustic music lacks, but subtlety goes

right out the door. The more noble sentiments, strength, courage,

tenderness, pathos, joy, tragedy - these are stifled. Shakti is the proper

form for their expression."

McLaughlin, since leaving Chinmoy's Centre, has voyaged through India and

returned more secular. His hair is its longest in eight years. He now

indulges in an occasional cigarette or taste of wine or beer. And, after

his second marriage split up last fall (that wife was also in the ashram

and helped him run a restaurant in Queens), he finds, "I like to have

pretty woman around me - who doesn't?"

John hasn't completely severed with Chinmoy, but is no longer a disciple.

"I love him very much, but I must assume responsibility for my own

actions. When my sweet wife walked out on me, that catalyzed everything,"

he explains. (His first marriage produced a son, Julian, now 11, living in

England, whom "I don't see as much as I'd love to. We are pals, sort of at

the 'hanging out' stage.")

McLaughlin's loft reflects the serenely uncomplicated daily life that

provides easy access to higher states. Coffe table books tend to be erudite

tomes on Eastern mysticism. There is a meditation area with a bronze of

Buddha's wife nestled among a half-dozen trees, and McLaughlin takes a

simple delight in watering the plants. He relishes cooking Indian or

Italian, and dries his wash on a line near his Ping-Pong table. His more

violent pastimes include scuba-diving and sking.

The youngest of five children, John was born in Yorkshire, England, but

moved at age 7, with his mother, to a tiny seacoast village just south of

Scotland when his parents split. His father, a turbo-engineer, wanted John

to follow him, but recalls McLaughlin, "I got almost everything from my

mother, a violinist - and my brothers. They were Ph.D.s, intellectuals,

great debaters. I remember very little about my father."

McLaughlin's first guitar at 11 was a hand-me-down. Three years of

classical piano study helped him "cop everybody's licks off records -

Leadbelly, Coltrane, Krupa, Miles Davis, Oscar Peterson, Tal Farlow, Muddy

Waters." By 16, he'd quit school and gone to work in a guitar repair shop,

until a friend coaxed him to gig on the road that led to London.

McLaughlin's heaviest dues there were in recording and TV sessions, where

he played "plug-in, you-name-it, chinky, toppy, computerized guitar" for

Humperdinck, Bacharach, Anka, Nero and Warwicke. In 1970 his growing rep

led him to join Miles Davis on his famous Bitches Brew LP. By then

McLaughlin, already an occult probing the eastern religions, yoga,

psychedelic drugs and astral projections, had met Chinmoy and "begun the

awesome task of searching for self-awareness."

"The artist, mad fool that he is," says McLaughlin, "is intuitively

aware that what is inside him is real - The Truth. I believe one can know

the unknowable, but only in perfect silence. We realize the utter futility

of trying to speak the unspeakable," he says. "But there is a delightful

pointlessness and mystery about it that makes life so beautiful."

|